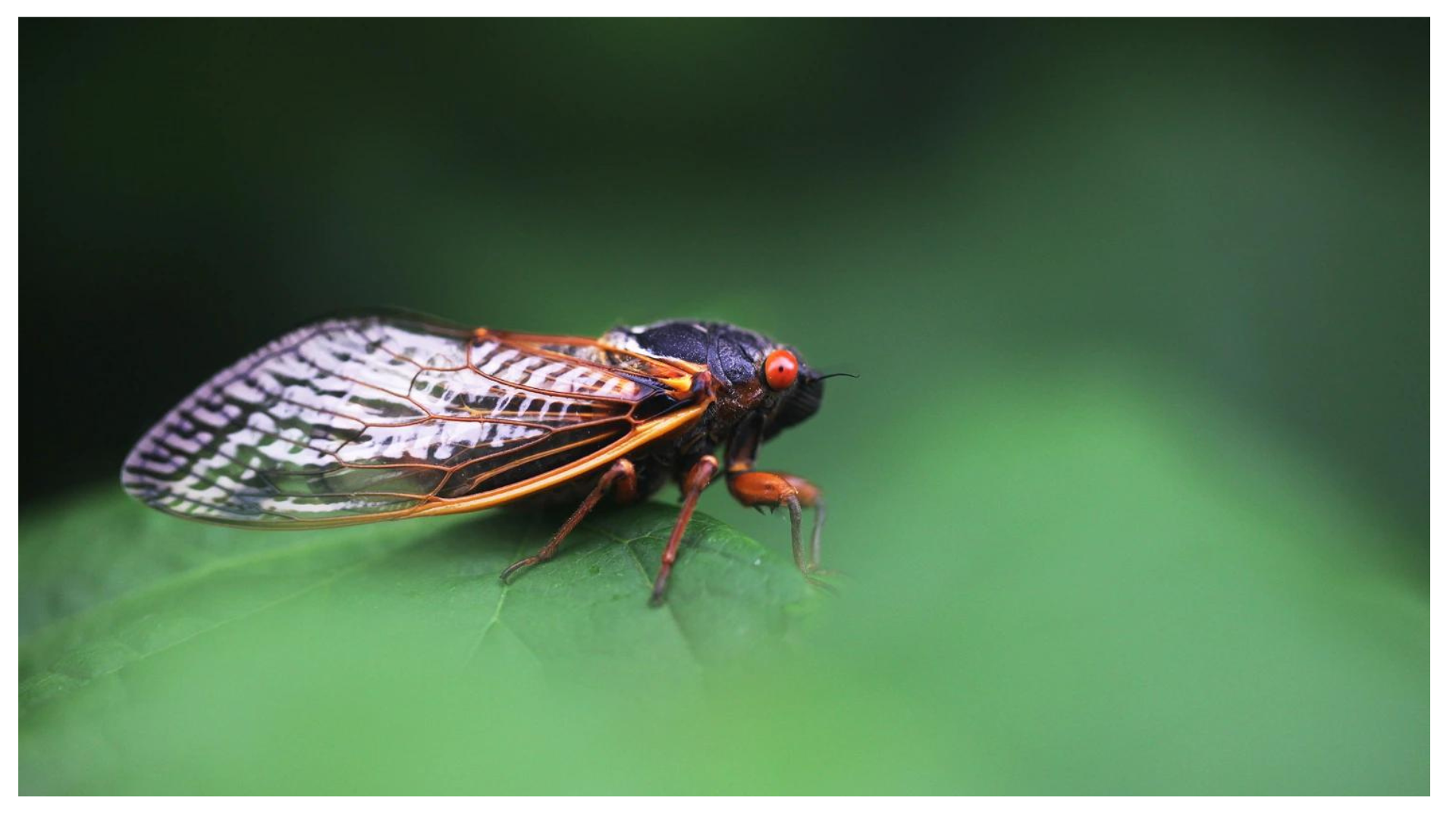

When billions of periodical cicadas emerge in a rare double occurrence, they disrupt the food chain for other species.

This April, billions of periodical cicadas began their descent on the midwest and southeast of the United States, causing so much noise that local people called the police to complain. However, the cicadas not only disrupt communities with their thunderous symphony, but they also cause havoc in food chains.

After spending more than a decade below drinking tree root liquids, two broods—Brood XIII and Brood XIX—will emerge concurrently in 2024, the first time this has happened since 1803.

According to Grace Soltis, a PhD student researching evolutionary biology at Florida State University, the appearance of insects in large numbers would destabilize natural food systems.

“Cicada emergences can completely rewire a food web,” adds Soltis, who co-wrote a paper about the cascading effects of bird predation on cicadas during the 2021 Brood X emergence. “For predators, these emergences represent a massive increase in resources. It’s essentially an all-you-can-eat buffet for ravenous predators.”

According to Soltis, the emergence would have little direct influence on the human food chain, but extremely high levels of cicadas are bad news for everyone. So scientists are using 2024’s twin emergence to learn more about the insects’ impact on other species, both in the animal realm and in plants.

Periodical cicadas have a far longer life cycle than their non-periodic counterparts, which mature each summer. After hatching, young periodical cicadas, known as nymphs, spend 13 to 17 years underground eating on roots before wriggling upwards and maturing into adults.

The 17-year-old Brood XIII, which hatched in 2007, is expected to emerge in Northern Illinois, while the 13-year-old Brood XIX will emerge in regions of the southeastern United States. Both events began as expected in late April 2024.

The insects will create a delicious feast for several types of fauna. Birds of many shapes and sizes, including sparrows, crows, and swallows, adapt their diets to take advantage of the cicada banquet. Research released in 2023 discovered that the emergence of periodic cicadas alters the diet of whole bird populations.

Mass cicada emergences may cover up to 190,000 square miles (500,000 square kilometers), according to John Lill, a biology professor at George Washington University’s department of biological sciences and co-author of the cascade research. As a result, this diet shift has a knock-on impact across the food chain: “It’s a pretty significant disruption across a whole landscape,” he adds, “and generalist predators switch over to feeding on this bounty of food.”

Scientists discovered that wild turkeys, for example, will capitalize on the abundance, resulting in a wild turkey boom. According to Lill, cicadas are eaten by shrews, a little mole-like mammal, as well as bats, spiders, wasps, and even snakes.

The disruptive effects, however, have the most visible influence on birds. According to Soltis and Lill’s research, more than 80 bird species shifted to eating cicadas during the 2021 emergence.

The scientists realized that what the birds did not consume was equally as essential as what they did. Caterpillars, which are often eaten by birds, were removed from the dinner menu, and their population more than quadrupled. This, in turn, resulted in tree damage caused by overgrown caterpillar populations.

“There are consequences for the food web because of all the things that go uneaten,” Lill asserts.

What will be the long-term consequences of the 2024 Cicada Bonanza?

According to Lill, it is still unclear how long it takes for the food chain to calm down and return to normal. The birds resume their normal diets soon after the cicada emergence ends, but since there is so much food available, bird populations grow. A knock-on impact occurs the next year, when food sources are less numerous.

“There have been relatively few studies documenting long-term bird data when it comes to cicada emergences,” says Lill.

Emergence episodes endure just five to seven weeks, but they provide a unique chance for scientists to study the effects of a “resource pulse”—a h huge increase in resource availability over a short period of time. Cicadas are believed to promote soil nutrient cycling, partially because their corpses decompose and release nutrients, and also because the emergence holes they leave increase water penetration into the soil. Despite this, little is known about how living cicadas affect food webs in real time.

Climate change will keep scientists on their toes as they watch the effects of the emergence of cicadas. The species have developed across significant periods of climatic change, and experts believe they will continue to adapt to a warmer world.

Experts anticipate that rising temperatures may cause periodic cicada emergences to begin earlier in the year, as well as an increase in unexpected “oddly-timed” emergences.

“The effects of climate change on cicadas and their food webs remain to be seen,” Soltis states. “I hope we can collect more data on this during these emergences.”